Chronic Pain Therapy: Retraining Your Brain

Chronic pain is living in a body that feels like both home and prison, carrying exhaustion that sleep cannot touch and hurt that others cannot see. It is the weight of unspoken grief for the life you once had, and the quiet strength of pushing through when every step feels heavy.

Understanding Pain

Let’s start by saying your brain is trying to protect you.

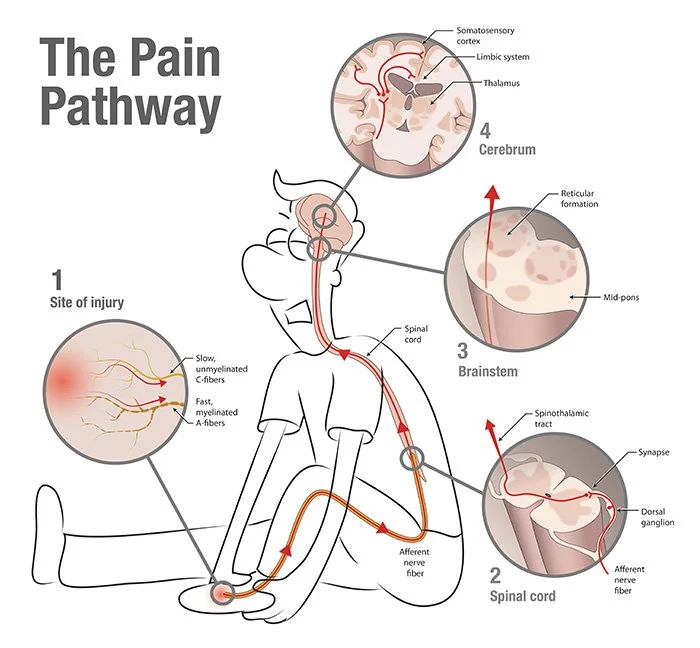

When an injury occurs, sensory nerves carry pain signals to the brain through two main pathways. Fast, myelinated A-delta fibres transmit sharp, tingly, prickly immediate pain, triggering a quick response to potential danger (Dowd, 2007). In contrast, unmyelinated C-fibres conduct more slowly carrying dull, aching, or burning pain that lingers, this reinforcing the need for rest and healing (Dowd, 2007).

Before these signals reach the brain, they first pass through the spinal cord, where they are processed and either amplified or modulated. From there, they travel through the brainstem, which plays a role in automatic responses like heart rate and breathing, before reaching the cerebrum. This is where the brain interprets the pain, assigns meaning to it, and decides how the body should respond.

This system has evolved to protect us, helping us avoid harm and recover from injury. However, sometimes it becomes dysregulated, meaning pain signals continue long after the initial injury has healed. When this happens, what was once acute pain transforms into chronic pain—not because the body is still damaged, but because the nervous system has learned to stay in a heightened state of sensitivity.

Central Sensitisation or Neuropathic Pain

I have had many clients come to me after being told by other medical professionals that their pain is "in their head." As someone who lives with chronic pain, I know how invalidating those words can be. However, after studying neuroscience, chronic pain, and trauma in more depth, I suspect what some medical professionals may actually mean is that pain is influenced by the brain—though this message is often poorly communicated.

There is a saying: "Neurons that fire together wire together." This means that when certain nerve pathways are repeatedly activated, they strengthen over time, making it easier for those signals to travel. When it comes to chronic pain, the nervous system learns to be highly responsive, remaining on high alert even when there is no immediate danger. At first, this can be protective, helping to prevent further injury. But over time, it can cause the brain to amplify pain signals, even in the absence of a real threat.

This process is known as central sensitisation or neuropathic pain, and it occurs because of changes in both the spinal cord and the brain.

The spinal cord plays a crucial role in transmitting pain signals from the body to the brain. Within the dorsal horn, incoming pain signals activate afferent nerve fibers, leading to the release of neurotransmitters and neuropeptides (Cheng, 2011). In chronic pain states, this process triggers inflammatory and neuropathic changes, altering the structure and function of local neural circuits (Cheng, 2011). As a result, the dorsal horn becomes sensitised, increasing its responsiveness and amplifying pain signals sent to the brain, contributing to persistent pain perception.

At the same time, key areas in the brain responsible for pain perception are modified. Here's how chronic pain can impact various brain regions:

Prefrontal Cortex: This area helps us make decisions and manage our reactions. Chronic pain can reduce its activity, making it harder to cope with pain and regulate emotions.

Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): The ACC processes pain and emotions. In chronic pain conditions, it often becomes more active, which can heighten the perception of pain.

Amygdala: Known as the brain's threat detector, the amygdala can become hyperactive in chronic pain states, leading to hypervigilance, increased anxiety, and a heightened sense of threat from pain.

Hippocampus: Essential for memory and learning, the hippocampus may undergo changes that affect memory formation and emotional responses in those with chronic pain.

(Yang & Chang, 2019)

These brain changes create a cycle where the nervous system becomes more sensitive to pain signals, making the pain feel more intense and persistent, even when no new injury is present. This is why chronic pain can feel relentless—it is not imaginary or "all in your head" but a real, measurable shift in how the nervous system functions. Recognising these changes does not make your pain any less valid; rather, it highlights the importance of comprehensive pain management strategies and opens the door to new ways of working with your nervous system to help bring it back into balance.

Neuroplastic Pain Therapy: Rewiring the Brain

The good news is that the brain and nervous system are neuroplastic, meaning they can adapt and change. Just as they learned to amplify pain, they can also learn to quiet it. Central sensitisation can be reduced, and with the right approach, it is possible to retrain the nervous system to become less reactive.

What does this mean?

It means there is hope. You are not stuck in pain forever.

When I begin working with someone experiencing chronic pain, we start with a thorough intake process. This helps me understand how pain is showing up for you, whether central sensitisation or neuroplastic pain is playing a role, and how much shock and trauma your body may be holding after prolonged distress.

From there, we map your pain experiences to build a clearer picture of how pain manifests in your body. This process allows us to create a personalised pain management plan—one that aligns with your unique pain scale. Having a plan in place for when pain is mild or when it reaches its most intense levels creates a sense of safety in the body. When the brain knows there is a plan, it can begin to reduce hypervigilance, which in turn helps lower pain sensitivity.

The next stages of therapy are tailored to each person’s needs, but they generally follow a structured approach, outlined below.

Somatic Tracking & Internal Family Systems

When pain levels are lower, we learn to ‘be with’ the sensations in our body, exploring them with curiosity and compassion. This fosters a deeper connection between the mind and body and is an important part of pain therapy. By observing your physical sensations with safety and curiosity and attending to your pain without fearful parts taking over, we can gently retrain your brain to reinterpret these signals, in time reducing the intensity and frequency of your pain.

This process aligns with both Somatic Tracking and Internal Family Systems (IFS). In IFS, we recognise that different ‘parts’ of us carry distinct emotions, beliefs, and protective strategies. When it comes to chronic pain, there are often parts of us that have developed hypervigilance around bodily sensations—parts that brace for pain, try to push through it, or fear what it might mean. These parts are not the enemy; they are trying to protect you. However, by tracking these parts and listening to them with compassion rather than resistance, we can help shift their roles, allowing them to relax.

Through somatic tracking, we can explore how different parts of us respond to pain—whether it is a part that feels helpless or one that numbs sensations altogether. By gently acknowledging these responses and reassuring the nervous system that we are safe, we create an internal environment where pain no longer needs to be the dominant experience. Over time, this mindful awareness can rewire the brain’s relationship with pain, restoring a sense of agency and ease in the body.

Deep Brain Reorienting and Pain

Deep Brain Reorienting (DBR) is a therapeutic approach that works with both the brain and body to heal the impact of shock. From my own experience, there have been moments when my pain has been so intense that it has instantly put my brain into ‘survival mode.’ Developed from Dr. Frank Corrigan’s neuroscience research, DBR supports the brain’s natural ability to process the physical imprints of shock and trauma associated with living with pain.

DBR works at the brainstem level, which governs our most instinctive responses to threat—even when that threat comes from within. It specifically targets the superior colliculus to process the experience of shock and the periaqueductal gray, the primary control centre for descending pain modulation (Yang & Chang, 2019).

Through DBR sessions, we can help the brain downregulate pain and establish a deep sense of safety at the brainstem level.

What next?

If you are living with chronic pain and feel stuck in a cycle that seems impossible to break, know that change is possible. Brain retraining, including Deep Brain Reorienting, offers a gentle way to work with your nervous system to reduce pain and restore a sense of safety in your body. If you are curious about how this approach could support you, I invite you to reach out. You do not have to navigate this alone—there are ways to help your brain and body find relief.

References:

Cheng, H. 2011. ‘Spinal Cord Mechanisms of Chronic Pain and Clinical Implications’. PubMed Central. 14(3):213–220. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0111-0

Dowd, F. 2007, Pain: Pathophysiology, in Enna, S & Bylund, B (Ed) in xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference, Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008055232-3.60644-0

Yang, S., & Chang, M. 2019. ‘Chronic Pain: Structural and Functional Changes in Brain Structures and Associated Negative Affective States’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20(13):3130. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133130